IN THE REAL TIME

Art: Jevijoe Vitug (@jevijoe)

Curator: Julia Stachura (@neonli)

Collaboration: AnkhLave Arts Alliance, Governors Island, New York

408 B Colonels Row, Governors Island, New York, NY

(https://ankhlavearts.org, @ankhlave)

Exhibition dates: August 24 – September 18

Curatorial texts + photographs: Julia Stachura

Colonizer and Bunots (after Hammons’ Real Time) Jevijoe Vitug

Colored window film, robot vacuum cleaner, bunot (coconut husk) 2024

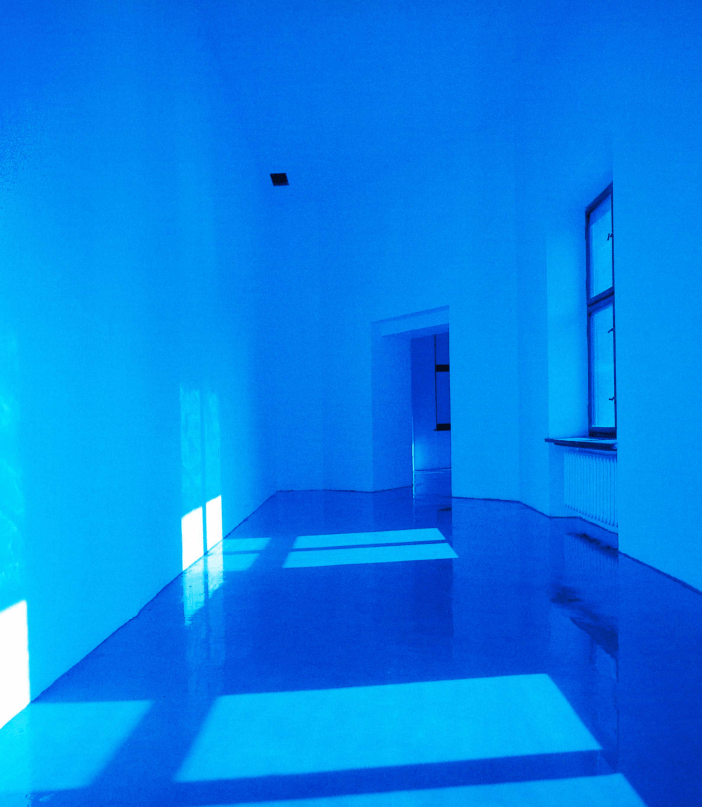

This site work contains window films, gradually changing the interior’s colors, coconut husk polishers in the Philippines called bunot, and an AI robotic vacuum cleaner. Vitug purposefully selected the color purple to encode ube, a sweet purple yam indigenous to the Philippines, that has become a popular staple treat in Little Manila, Queens. The color also transforms throughout the day shifting from purple to violet, deepening its hue, reminiscing of the ultraviolet light, invisible to the naked human eye. Turning light into an active creator of the site work, the visitor’s perception confronts the violet color of invisibleness, which ultimately affects the skin color of everyone present in the gallery space. In this sense, the window filters act as the mediator of cultural and social interactions based on the gaze*, reflecting what W.J.T. Mitchell described as seeing through race**, claiming that the color-blind world is neither desirable nor achievable. The color filling up the space creates an alien-like atmosphere, in which the artist is playing out a speculative scenario of a clash between bunots, coconut husks encapsulating the energy and wisdom of indigenous entities, and a foreign robot equipped with an artificial intelligence sensor for obstacle avoidance, representing colonizer. The dialogue between Vitug’s violet and David Hammons’ blue reflects Amber Jamilla Musser’s concept of the “architectures of blue,” which, in connection to brownness, engages with the ideas of labor migration***. Both artists utilize color and light to infuse them with cultural significance and to trace the process of becoming unseen by historical accounts and the eye of the other. The installation challenges the narrative of technological dominance over the overlooked traditional cultural practices and invisible labor while providing an insightful glare into the future, in which the endurance of skills, techne, thanks to indigenous knowledge, will provide survival, even when the whole world as we know it may have shut down.

Footnotes:

* Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan. Book IX, edited by Jacques-Alain Miller, translated by Alan Sheridan, (New York- London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1981).

** W. J. T. Mitchell, Seeing Through Race, Harvard University Press, 2012.

***Amber Jamilla Musser, Architectures of Blue: Race, Representation, and Black and Brown Abstraction, Brooklyn Rail, (https://brooklynrail.org/2017/10/art/Architectures-of-Blue-Race- Representation-and-Black-and-Brown-Abstraction).

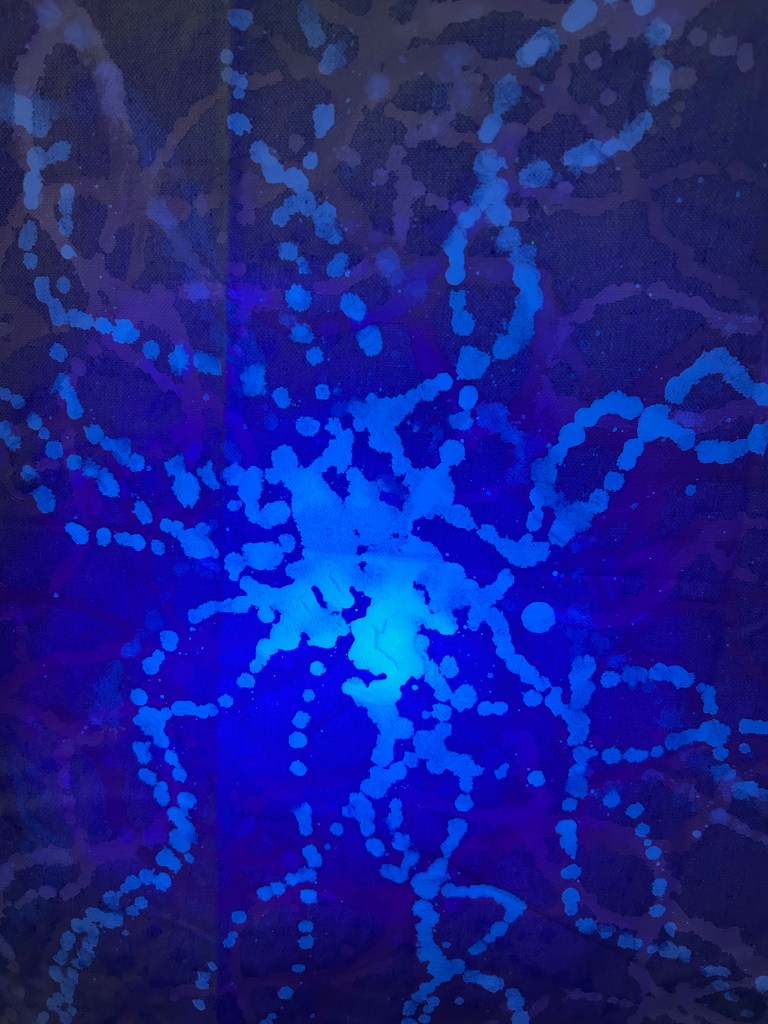

Suku (after Hammons’ Concerto in Black and Blue) Jevijoe Vitug

Canvas drop cloth, fluorescent/UV reactive paint, acrylic paint, 3D glasses, LED UV flashlights

2024

This site work focuses on indigenous wisdom and the limitations of the physical world. Suku is a word in Kapampangan, which is one of the major indigenous Austronesian languages in the Philippines. One of the meanings of suku is an indeterminate end, similar to the human brain’s neural network that has been wired constantly, seeking endlessly and indefinitely within the limits of our able bodies and available technologies. Vitug’s painting on unprimed and unstretched drop cloth hung from the ceiling and draped across the staircase keeps the patterns invisible to the naked eye. The UV flashlights and 3D glasses activate the painting’s hidden perceptual qualities, allowing for a virtual experience. The brain system reflected in the Suku also translates to the power energy pulsating throughout both the body and technology, allowing for sending information.

Similar to David Hammons’ Concerto in Black and Blue (2002), exhibiting nothing in a space engulfed in the darkness, lightened by participants’ flashlights, Vitug delves into the limitation of physical bodies in limited space. Either Hammons’ Concerto playing with the historically exclusive implications of the white cube or Vitug’s site works exhibited at formerly military barracks at Governors Island; the artists indirectly address the embedded codes on blackness and indigeneity. As Maya Angelou put it: “We need to haunt the halls of history and listen anew to the ancestors’ wisdom.*”

Footnotes:

*Maya Angelou, I Dare to Hope published in The New York Times, August 25, 1991.

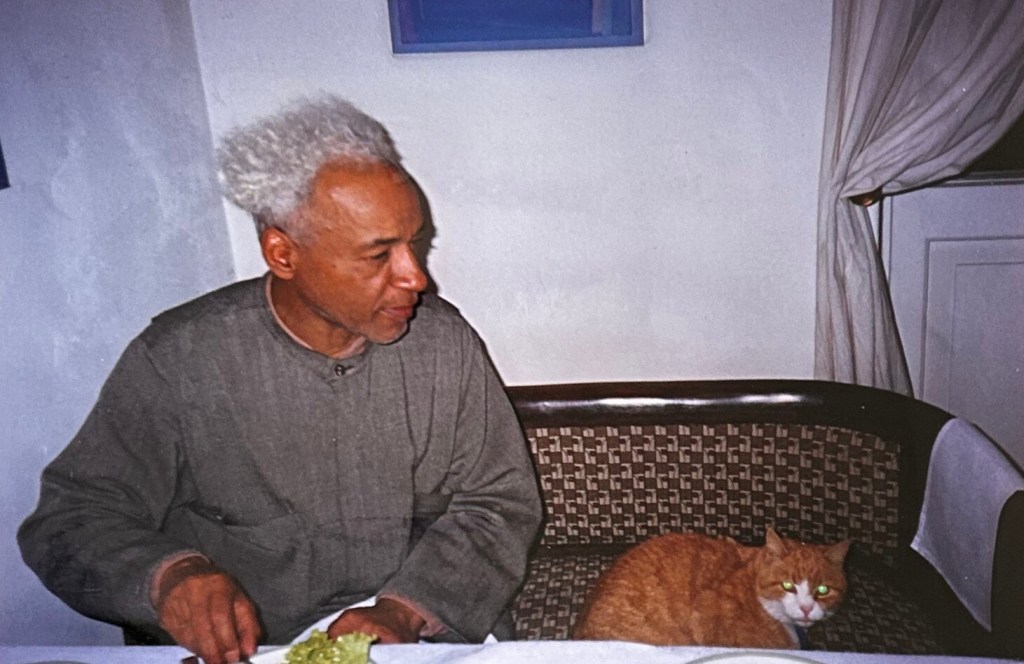

Archival photographs of David Hammons in Warsaw, 2000. Courtesy of the curator of the Real Time exhibition, Milada Ślizińska. Photographs taken by Józef Mrozek in the domestic space of the curator’s apartment.

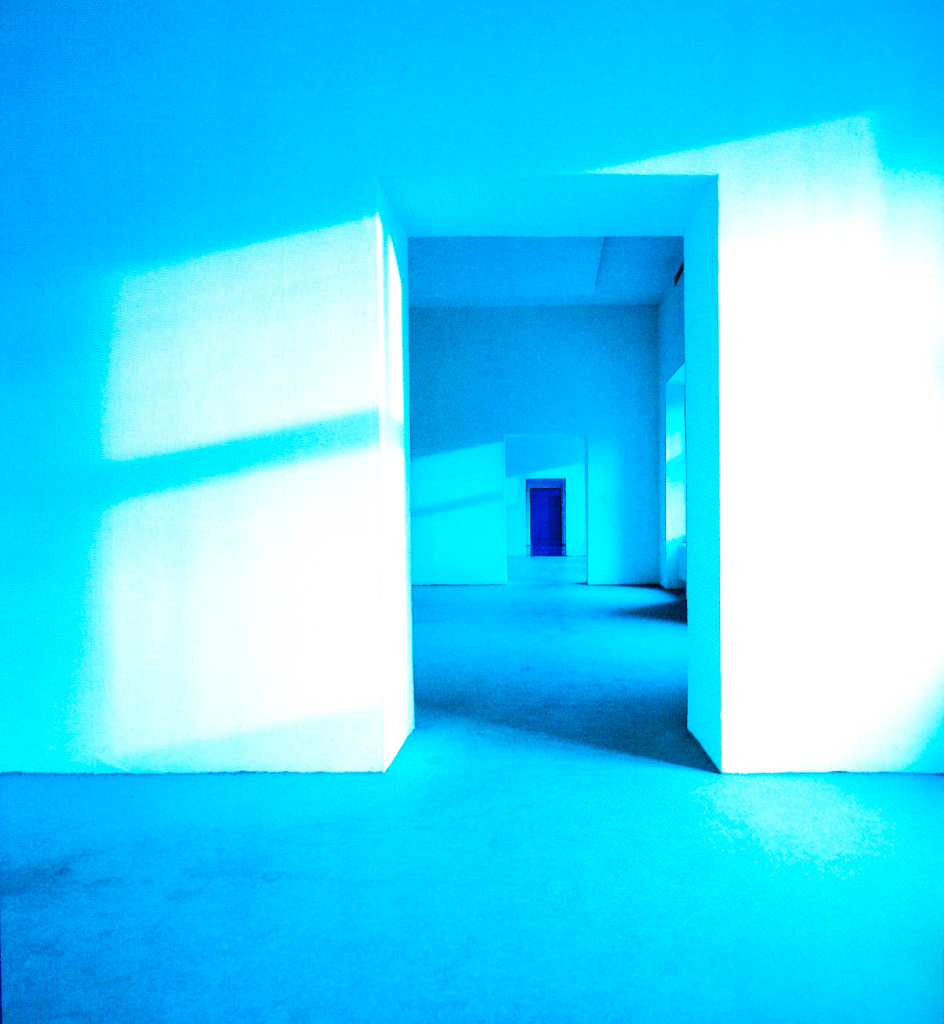

Blackness in Hammons’s work is a matter of blue*, writes Fred Moten. The conceptualized idea of invisible heritage became the starting point for David Hammons’ installation Real Time, realized in 2000 at the Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw, Poland, curated by Milada Ślizińska. The gradient filters covering the castle’s windows, filling up the space with blue light, along with flooded floors, transformed both the spatial conditions of the interior and impacted the visitor’s perception. As Darby English points out, to experience and see Hammons’ work, one must become part of it**. The color blue encompassed emotions and cultural music code, blue – sad, blue – blues***, as Ślizińska wrote. The blues, combining spiritual songs, field hollers, and call-and- response sequences, is a language in itself, bearing echoes of the struggle against racial oppression and the melancholy resulting from the sound of blue notes, characterized by a lowered tonality. Throughout the filters, transmitting light at different intensities and layers of cultural meanings, Hammons sublimely comments on the historical invisibility of African Americans in cultural institutions, referring to racial segregation, characterized by sociologist and historian W.E.B Du Bois as a color line****. The real time spent in the gallery space for some was a time of contemplation and exploration, while for others, it was a time of confusion while searching for the artworks that were nowhere to be seen. The simple act of drowning the space in blue has turned ephemeral light into something almost tangible and solid, mediating dialogue between the public space and the visitors’ bodies, becoming moving and breathing works of art.

Footnotes:

*Fred Moten’s lecture in Wattis Institute, March 10, 2017, from: David Hammons In Our Mind.

** Darby English, How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness, MIT Press, Cambridge 2010, p. 1.

***David Hammons, Real time. 09.05.2000-18.03.2000, trans. B. Pugacz-Muraszkiewicz, text by M.Ślizińska, Ujazdowski Castle, Warsaw, 2000.

****The term color line was used by W.E.B. Du Bois in his now-canonical 1903 book, The Souls of Black Folk, but first appeared in an article by African-American abolitionist Frederick Douglass – The Color Line – published in the North American Review magazine in 1881. See: W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, 1903, The Project Gutenberg eBook: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/408/408- h/408-h.htm; Frederick Douglass, The Color Line, “The North American Review,” 1881, no. 132, pp. 567-77, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25100970.

“Real Time” exhibition in Warsaw, Poland, 2000, archival photographs from the catalog.

Leave a comment